Atomic Line Spectra

Light carries energy in discrete packets. Planck’s constant h appeared in black-body radiation and the photoelectric effect, showing that energy is quantized. But if light is quantized, what does this tell us about the atoms that emit and absorb light?

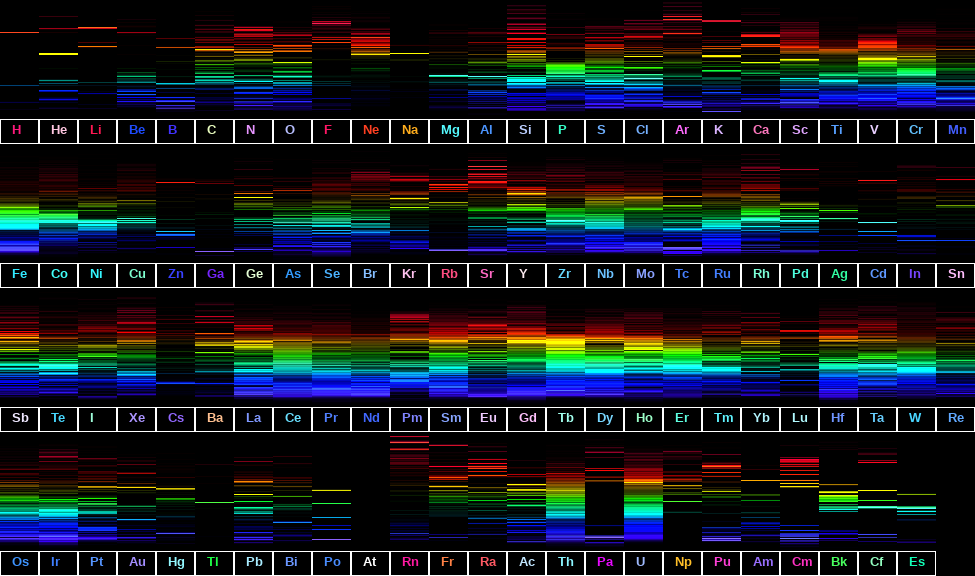

Heat different elements in a flame and they glow with characteristic colors. Pass that light through a prism and instead of a smooth rainbow, each element produces its own pattern of discrete bright lines. These patterns, called line emission spectra, are made up of spectral lines at specific wavelengths. Each element has a distinctive pattern that serves as its fingerprint.

What determines these patterns? Why do atoms emit only certain wavelengths? This question puzzled physicists for decades. The answer turned out to depend on how electrons are arranged within atoms.

Continuous vs Line Spectra

Not all glowing objects produce the same type of spectrum. Heat a solid piece of metal until it glows, and it produces light at all wavelengths. This is a continuous spectrum, the same black-body radiation we discussed in the previous chapter. Dense gases and liquids also produce continuous spectra when heated.

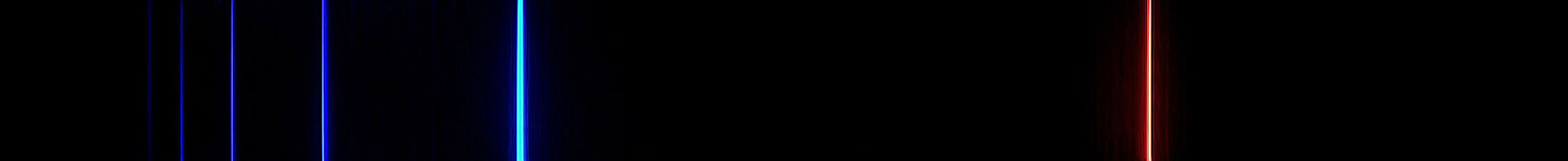

But heat a low-pressure gas, and something different happens. Instead of emitting all wavelengths, the gas emits only specific wavelengths, producing a line spectrum. Sodium vapor lamps (the yellow streetlights) emit primarily two closely spaced lines at 589.0 nm and 589.6 nm. Neon signs glow red-orange from several lines in the visible spectrum. Hydrogen gas discharge tubes emit four prominent lines in the visible region: red, blue-green, blue, and violet.

Why do isolated atoms in a gas emit only certain wavelengths?

The Historical Puzzle

By the late 1800s, spectroscopy had become a precise experimental science. Physicists could measure spectral line wavelengths to many decimal places. In 1885, a Swiss schoolteacher named Johann Balmer noticed that the wavelengths of hydrogen’s four visible spectral lines weren’t random. They followed a mathematical pattern involving simple integers and a single constant. Johannes Rydberg later generalized Balmer’s formula to predict additional spectral lines.

The formulas worked perfectly, matching experimental wavelengths exactly. But why? What determined these particular wavelengths? Why integers? Classical physics offered no explanation.

Worse, classical physics made a disastrous prediction. According to classical electromagnetism, an electron orbiting a nucleus is a charged particle undergoing acceleration (circular motion). Accelerating charges radiate electromagnetic energy. This means electrons should continuously lose energy, spiraling inward and crashing into the nucleus in about 10−11 seconds. Atoms should be completely unstable.

Yet atoms don’t collapse. The chair you’re sitting on exists. But classical physics couldn’t explain why.

Bohr’s Radical Solution

In 1913, Danish physicist Niels Bohr proposed a model that explained both the stability of atoms and the discrete spectral lines. Bohr imagined the atom as a miniature solar system: a dense, positively charged nucleus at the center with electrons circling around it like planets orbiting the Sun. But unlike planets, which can orbit at any distance, Bohr proposed that electrons are restricted to specific orbits at fixed distances from the nucleus.

His model was radical because it simply declared that certain rules of classical physics don’t apply at atomic scales.

Niels Henrik David Bohr: A Danish physicist (1885-1962) who won the Nobel Prize in Physics (1922) for his foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory. (Source: Wikipedia)

Bohr’s three postulates:

Stationary states: Electrons orbit the nucleus in specific allowed orbits called stationary states. While in these orbits, electrons do not radiate energy, despite classical physics predicting they should. “Stationary” refers to the energy, not the electron’s motion. The electron still moves, but its energy stays constant.

Quantized angular momentum: Bohr proposed that only orbits where angular momentum equals an integer multiple of h/(2π) are allowed:

\[L = mvr = n\dfrac{h}{2\pi} \quad \text{where } n = 1, 2, 3, \ldots\]

Here m is the electron mass, v is its speed, r is the orbital radius, and n is the principal quantum number, an integer that labels each allowed orbit. The quantity h/(2π) appears so frequently in quantum mechanics that it has its own symbol: ℏ (“h-bar”), the reduced Planck constant. Bohr’s condition becomes simply L = nℏ.

Why did Bohr choose this particular quantization? At the time, it was an inspired guess that made the mathematics work. The deeper reason emerged later when de Broglie showed that electrons behave as waves, and standing waves on a circular orbit require the circumference to equal a whole number of wavelengths (see the Wave-Particle Duality page). This wave condition leads directly to L = nℏ.

Linear momentum (p = mv) measures a moving object’s “oomph” based on its mass and speed. A truck moving at 30 mph has more momentum than a bicycle at the same speed.

Angular momentum (L) is the rotational equivalent. It measures an object’s “rotational oomph” when moving in a circle. For an object in circular motion:

\[L = mvr\]

where m is mass, v is speed, and r is the radius of the circle.

Why does radius matter? Think of a figure skater spinning. When she pulls her arms in (smaller r), she spins faster (larger v). When she extends her arms (larger r), she slows down (smaller v). The product mvr stays constant. This is conservation of angular momentum.

For an electron orbiting a nucleus, angular momentum captures both how fast the electron moves and how far it is from the nucleus. Bohr’s radical claim was that L can’t have just any value. It must be a whole-number multiple of h/(2π). This restriction determines which orbits are allowed and therefore which energies the electron can have.

- Quantum jumps: Electrons can transition between stationary states by emitting or absorbing a photon. The photon’s energy equals the energy difference between the states:

\[\Delta E = h\nu\]

Planck’s constant h appears in the quantization condition. The same constant from black-body radiation and the photoelectric effect now determines which atomic orbits are allowed.

Bohr’s model directly addressed the classical physics problems. Electrons don’t spiral into the nucleus because only certain orbits are allowed, and electrons in these orbits don’t radiate. The quantization of angular momentum determines which orbits exist. Atoms emit discrete spectral lines because transitions occur between discrete energy levels.

The integer n = 1 labels the orbit closest to the nucleus, called the ground state, the lowest energy state of the atom. Higher values (n = 2, 3, 4, …) label excited states, orbits with progressively higher energy. An electron can only exist in one of these allowed states, never between them. We’ll see why when we treat electrons as waves.

Energy Levels in Hydrogen

Using his postulates, Bohr derived an expression for the energy of an electron in each allowed orbit of the hydrogen atom:

\[E_n = -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n^2}\]

where R∞ is the Rydberg constant (1.09737 × 107 m−1), h is Planck’s constant (6.626 × 10−34 J s), c is the speed of light (2.998 × 108 m s−1), and n is the principal quantum number.

This formula works exactly for hydrogen. Other atoms are more complex, as discussed below.

Two versions of the Rydberg constant appear in different textbooks and references:

R∞ (Rydberg constant) = 1.09737 × 107 m−1

This is the value that emerges directly from the Bohr model derivation. It assumes the nucleus is stationary while the electron orbits around it.

RH (Rydberg constant for hydrogen) = 1.09678 × 107 m−1

This is R∞ corrected for the actual motion of the proton.

Why does nuclear mass matter?

The Bohr model assumes the electron orbits a stationary nucleus. But the nucleus is not truly stationary. Because the electron exerts a gravitational and electrical pull on the proton, both particles actually orbit around their common center of mass.

Think of two ice skaters holding hands and spinning. If one skater is much heavier, the lighter one does most of the moving while the heavier one barely shifts. The proton is about 1836 times heavier than the electron, so the proton moves very little, but it does move. This small motion slightly changes the energy levels.

To account for this two-body motion mathematically, we replace the electron mass with the reduced mass:

\[\mu = \dfrac{m_e \cdot m_p}{m_e + m_p}\]

When the nucleus is infinitely heavy (mp → ∞), the reduced mass equals the electron mass and we get R∞. For real hydrogen with its finite-mass proton, we get RH, which is about 0.05 % smaller than R∞.

Which constant should you use?

The wavelength differences between the two constants are less than 1 nm. For introductory calculations, either constant gives acceptable results. This text uses R∞ because it connects directly to the theoretical derivation.

The negative sign in this formula requires explanation.

Energy is defined relative to a reference point. For atoms, we choose zero energy to represent a free electron at rest infinitely far from the nucleus. This is the ionized state: electron and nucleus are separated.

When an electron is bound to the nucleus, its energy is negative. Negative energy means the electron is trapped in the attractive electrical potential of the nucleus. The more negative the energy, the more tightly bound (more stable) the electron is.

Consider the ground state of hydrogen (n = 1):

\[ \begin{align*} E_1 &= -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n^2}\\[1.5ex] &= -\dfrac{(1.0973\bar{7} \times 10^{7}~\mathrm{m^{-1}})(6.62\bar{6}\times 10^{-34}~\mathrm{J~s})(2.99\bar{8}\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}})}{1^2} \\[1.5ex] &= -2.1\bar{8} \times 10^{-18}~\mathrm{J} \left ( \dfrac{\mathrm{eV}}{1.602\bar{2} \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J}} \right ) \\[1.5ex] &= -13.6~\mathrm{eV} \end{align*} \]

This −13.6 eV is the ionization energy of hydrogen from the ground state. You must add at least 13.6 eV of energy to remove the electron completely (raise it to E = 0).

As n increases, energy becomes less negative (closer to zero), meaning the electron is less tightly bound. At n = ∞, E = 0, and the electron is free.

Energy levels are not evenly spaced. The spacing between consecutive levels decreases as n increases. The levels converge toward E = 0 at n = ∞, the ionization threshold.

Emission and Absorption

Atoms interact with light through two complementary processes: emission and absorption.

Emission occurs when an electron in an excited state (higher n) drops to a lower energy state, a process called relaxation. The energy difference appears as a photon:

\[\Delta E_{\text{electron}} = E_{\text{final}} - E_{\text{initial}} < 0\]

The electron loses energy (negative ΔE), and this energy is carried away by the emitted photon. The photon’s energy equals the magnitude of the energy change:

\[E_{\text{photon}} = h\nu = \dfrac{hc}{\lambda} = |\Delta E|\]

Absorption is the reverse process, called excitation. An electron absorbs a photon and jumps from a lower energy level to a higher one:

\[\Delta E_{\text{electron}} = E_{\text{final}} - E_{\text{initial}} > 0\]

The photon must have exactly the right energy to match the energy difference between levels. If the photon energy doesn’t match any allowed transition, the atom cannot absorb it.

This selectivity explains why spectral lines work as element fingerprints. Each element has a unique set of energy levels, producing a unique set of transition energies, and therefore a unique set of spectral line wavelengths.

Emission and absorption produce complementary spectra. An emission spectrum shows bright lines on a dark background (the wavelengths the atom emits). An absorption spectrum shows dark lines on a continuous background (the wavelengths the atom absorbs from white light passing through it).

A famous example of absorption spectra appears in sunlight. When light from the hot solar interior (which produces a continuous spectrum) passes through the cooler gases in the solar atmosphere, atoms in those gases absorb specific wavelengths. The resulting dark lines, called Fraunhofer lines after their discoverer, allowed astronomers to identify elements in the Sun, including helium (which was discovered in the Sun before being found on Earth).

The Rydberg and Balmer Equations

The Rydberg Equation

The Rydberg equation (or Rydberg formula) calculates the wavelength of light emitted or absorbed when an electron transitions between any two energy levels in a hydrogen atom:

\[\dfrac{1}{\lambda} = R_\infty \left ( \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{f}}^2} - \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{i}}^2} \right )\]

where

- λ is the wavelength of light

- R∞ is the Rydberg constant (1.09737 × 107 m−1)

- ni is the initial energy level (before transition)

- nf is the final energy level (after transition)

For emission, ni > nf (electron drops to a lower level). For absorption, ni < nf (electron jumps to a higher level).

The Balmer Equation

The Balmer equation is a special case of the Rydberg equation for transitions ending at nf = 2. These transitions produce the visible lines in hydrogen’s spectrum:

\[\dfrac{1}{\lambda} = R_\infty \left ( \dfrac{1}{2^2} - \dfrac{1}{n^2} \right ) \quad \text{for } n = 3, 4, 5, \ldots\]

where n is the initial energy level (n > 2).

Johann Balmer discovered this equation empirically in 1885 by analyzing the pattern in hydrogen’s visible spectral lines. He had no idea why it worked. Bohr’s model, nearly 30 years later, revealed that Balmer’s formula was a consequence of quantized energy levels.

The Rydberg equation follows directly from Bohr’s energy level formula.

Starting point: Bohr’s energy levels for hydrogen:

\[E_n = -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n^2}\]

Step 1: Calculate the energy difference between two levels.

For a transition from ni to nf:

\[\Delta E = E_{n_{\mathrm{f}}} - E_{n_{\mathrm{i}}} = -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n_{\mathrm{f}}^2} - \left(-\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n_{\mathrm{i}}^2}\right) = R_\infty hc\left(\dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{i}}^2} - \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{f}}^2}\right)\]

Step 2: Relate energy to wavelength.

The photon energy equals the magnitude of the energy change:

\[E_{\text{photon}} = |\Delta E| = \dfrac{hc}{\lambda}\]

Step 3: Solve for 1/λ.

\[\dfrac{hc}{\lambda} = R_\infty hc\left|\dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{i}}^2} - \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{f}}^2}\right|\]

Dividing both sides by hc:

\[\dfrac{1}{\lambda} = R_\infty\left|\dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{i}}^2} - \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{f}}^2}\right|\]

Step 4: Write in standard form.

For emission (ni > nf), the quantity in parentheses is negative, so we swap the order to make it positive:

\[\dfrac{1}{\lambda} = R_\infty \left ( \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{f}}^2} - \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{i}}^2} \right )\]

This is the Rydberg equation. Balmer’s empirical formula is recovered by setting nf = 2. The mysterious constant Balmer discovered is exactly R∞, the Rydberg constant that emerges from Bohr’s theory.

The Hydrogen Spectral Series

Transitions in hydrogen are organized into series based on the final energy level (nf). Each series appears in a different region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The Balmer series is the visible portion of hydrogen’s emission spectrum. The four prominent lines (red, blue-green, blue, violet) are the lines Balmer fit with his empirical formula in 1885, before anyone understood atomic structure.

- Lyman series: Transitions from n > 1 to n = 1 (UV region, 91-122 nm)

- Balmer series: Transitions from n > 2 to n = 2 (visible region, 365-656 nm)

- Paschen series: Transitions from n > 3 to n = 3 (IR region, 820-1875 nm)

- Brackett series: Transitions from n > 4 to n = 4 (far IR)

- Pfund series: Transitions from n > 5 to n = 5 (far IR)

Bohr’s model finally explained why Balmer’s 1885 formula worked. The empirical pattern Balmer discovered through trial and error emerged naturally from quantized energy levels. The Rydberg constant that appeared in Balmer’s formula was no longer a mysterious fitting parameter but a fundamental atomic constant derived from first principles.

Each series has a series limit, the shortest wavelength in that series, which occurs when ni → ∞. As relaxations originate from higher and higher n levels, the emitted wavelengths converge toward this limit. The Lyman series limit (91.2 nm) is particularly important because Lyman relaxations end at n = 1, the ground state. This limit corresponds to exactly 13.6 eV, the binding energy of ground-state hydrogen (E1 = −13.6 eV). A photon at 91.2 nm has just enough energy to ionize a ground-state hydrogen atom. Photons with shorter wavelengths (higher energy) don’t produce spectral lines; they ionize the atom instead of exciting it to a bound state.

Explore the spectral series interactively below. Select a series to highlight its transitions, or view all series together. Hover over any arrow to see the transition details and wavelength.

Different series appear in different spectral regions because of the energy level spacing. Transitions to n = 1 (Lyman series) involve the largest energy differences, producing UV photons. Transitions to n = 2 (Balmer series) have smaller energy differences, producing visible photons. Transitions to higher n involve even smaller energy differences, producing infrared photons.

Why Hydrogen?

Everything so far has focused on hydrogen. This isn’t arbitrary. Hydrogen is the simplest atom: one proton, one electron, no complications. The Bohr model gives exact quantitative predictions for hydrogen.

But what about other elements?

Other atoms do produce line spectra. Sodium has its characteristic yellow doublet. Helium, neon, mercury all produce distinctive patterns. But the Bohr model cannot quantitatively predict their spectra. Multi-electron atoms are far more complex because:

- Electrons repel each other (electron-electron repulsion)

- Inner electrons partially block (shield) the nuclear charge from outer electrons

- Electrons in different types of orbits (we’ll learn about s, p, d, f orbitals later) have different energies even at the same n

The Bohr model works only for hydrogen-like ions: species with one electron but a nuclear charge Z greater than 1. Examples include He+ (helium with one electron removed), Li2+ (lithium with two electrons removed), and Be3+. For these ions, the Bohr formula becomes:

\[E_n = -\dfrac{Z^2 R_\infty hc}{n^2}\]

where Z is the nuclear charge (number of protons). Larger Z means more tightly bound electrons and larger energy differences between levels. For example, He+ (Z = 2) has energy levels 4× more negative than hydrogen at the same n, and its spectral lines have 4× the energy (shorter wavelengths) of the corresponding hydrogen transitions.

Multi-electron atoms require quantum mechanics, which we’ll cover after wave-particle duality. The Bohr model, despite its limitations, established that atomic energy levels are quantized. This quantization produces the discrete spectral lines we observe.

The Significance of Planck’s Constant

Planck’s constant h appears throughout quantum phenomena:

- Black-body radiation: Planck’s law quantized electromagnetic radiation, E = hν

- Photoelectric effect: Einstein showed light carries energy in photon packets, E = hν

- Atomic structure: Bohr quantized angular momentum, L = nh/(2π), and energy levels depend on h through RHhc

- Photon emission/absorption: Transitions between atomic levels emit or absorb photons with E = hν

Planck’s constant is a fundamental constant of nature that sets the scale of quantum effects. It appears wherever quantization matters.

The value h ≈ 6.626 × 10−34 J s is extremely small, which is why we don’t notice quantum effects in everyday life. At macroscopic scales, energy differences are so large compared to hν that we don’t perceive the discrete steps. But at atomic scales, h sets the size of energy differences between allowed states.

For atoms to emit photons with discrete energies (E = hν), atomic energy levels themselves must be discrete. Quantization of light requires quantization of matter. These are two aspects of the same phenomenon.

But why are only certain energies allowed? The Bohr model gives no physical reason. The next chapter reveals what’s missing: electrons behave as waves.

Applications of Atomic Spectroscopy

Line spectra aren’t just a physics curiosity. They have practical applications across chemistry, astronomy, and technology. They all depend on one fact: each atom has a unique spectral fingerprint determined by its quantized energy levels.

Flame tests are a classic qualitative analysis technique in chemistry. When compounds containing specific elements are heated in a flame, the heat excites electrons to higher energy levels. As they return to lower levels, they emit light at characteristic wavelengths. Sodium produces yellow (589 nm), strontium produces red, copper produces blue-green, barium produces green, potassium produces lilac. These colors arise from specific electronic transitions in the atoms. Fireworks use the same principle: different metal salts produce different colors.

Astronomical spectroscopy allows us to determine what stars are made of. Every star produces a spectrum. By analyzing which wavelengths are absorbed (Fraunhofer lines in stellar spectra), astronomers identify which elements are present in stars. The spectrum also reveals the star’s temperature (from the overall spectral distribution), composition (from line identities and strengths), velocity (from Doppler shifts of lines), and even magnetic field strength. Helium was discovered in the Sun in 1868 by analyzing its spectrum, before anyone found helium on Earth.

Analytical chemistry uses spectroscopy to identify and quantify elements in unknown samples. Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) measures how much light a sample absorbs at specific wavelengths, determining element concentrations down to parts per billion. Emission spectroscopy analyzes light emitted when a sample is excited, identifying elements present.

Technology applications include emission lamps (sodium vapor streetlights emit primarily yellow light because of sodium’s 589 nm emission lines) and neon signs (different gases produce different colors). Lasers depend on transitions between specific energy levels, requiring population inversion (more atoms in an excited state than the ground state), which produces coherent light emission at a precise wavelength.

Practice Problems

Practice

Determine the energy (in J) of an electron in the n = 3 energy level as well as the n = 2 energy level of a single hydrogen atom.

Determine the energy change (ΔE in J) of the electron as well as the wavelength (in nm) of light produced when a 3 → 2 electronic transition occurs.

Solution

Energy for n = 3

\[ \begin{align*} E_3 &= -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n^2} \\[1.5ex] &= -\dfrac{(1.0973\bar{7} \times 10^{7}~\mathrm{m^{-1}}) (6.62\bar{6}\times 10^{-34}~\mathrm{J~s}) (2.99\bar{8}\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}})} {3^2} \\[1.5ex] &= -2.42\bar{2}1 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J} \\[1.5ex] &= -2.422 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J} \end{align*} \]

Energy for n = 2

\[ \begin{align*} E_2 &= -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n^2} \\[1.5ex] &= -\dfrac{(1.0973\bar{7} \times 10^{7}~\mathrm{m^{-1}}) (6.62\bar{6}\times 10^{-34}~\mathrm{J~s}) (2.99\bar{8}\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}})} {2^2} \\[1.5ex] &= -5.44\bar{9}7 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J} \\[1.5ex] &= -5.450 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J} \end{align*} \]

The energy at n = 2 is lower (more negative) than the energy at n = 3.

Energy change of electron

\[ \begin{align*} \Delta E &= E_2 - E_3 \\[1.5ex] &= (-5.44\bar{9}7 \times 10^{-19} - (-2.42\bar{2}1 \times 10^{-19}))~\mathrm{J} \\[1.5ex] &= -3.02\bar{7}6 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J} \\[1.5ex] &= -3.028 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J} \end{align*} \]

The electron is losing energy (ΔE is negative) as it transitions from the n = 3 energy level down to the n = 2 energy level.

Energy of photon

The electron lost 3.028 × 10−19 J of energy. This energy is carried away by the emitted photon, which has energy 3.028 × 10−19 J (positive, since the photon carries energy).

Wavelength of light

\[ \begin{align*} E_{\text{photon}} &= \dfrac{hc}{\lambda} \longrightarrow \\[1.5ex] \lambda &= \dfrac{hc}{E_{\text{photon}}} \\[1.5ex] &= \dfrac{(6.62\bar{6}\times 10^{-34}~\mathrm{J~s}) (2.99\bar{8}\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}})} {3.02\bar{7}6 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J}} \left ( \dfrac{10^9~\mathrm{nm}}{\mathrm{m}} \right ) \\[1.5ex] &= 656.\bar{1}2~\mathrm{nm} \\[1.5ex] &= 656.1~\mathrm{nm} \end{align*} \]

This is the red line in the hydrogen emission spectrum (the first line of the Balmer series, called H-alpha).

Practice

An electron in a hydrogen atom absorbs a photon with wavelength 121.6 nm. If the electron was initially in the ground state (n = 1), what energy level does it reach?

Solution

Energy of absorbed photon

\[ \begin{align*} E_{\text{photon}} &= \dfrac{hc}{\lambda} \\[1.5ex] &= \dfrac{(6.62\bar{6}\times 10^{-34}~\mathrm{J~s}) (2.99\bar{8}\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}})} {121.\bar{6}~\mathrm{nm} \left ( \dfrac{\mathrm{m}}{10^9~\mathrm{nm}} \right )} \\[1.5ex] &= 1.63\bar{3}6 \times 10^{-18}~\mathrm{J} \\[1.5ex] &= 1.634 \times 10^{-18}~\mathrm{J} \end{align*} \]

Initial energy (n = 1)

\[ \begin{align*} E_1 &= -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{1^2} \\[1.5ex] &= -\dfrac{(1.0973\bar{7} \times 10^{7}~\mathrm{m^{-1}}) (6.62\bar{6}\times 10^{-34}~\mathrm{J~s}) (2.99\bar{8}\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}})} {1^2} \\[1.5ex] &= -2.17\bar{9}89 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J} \\[1.5ex] &= -2.18\bar{0} \times 10^{-18}~\mathrm{J} \end{align*} \]

Final energy

After absorbing the photon:

\[ \begin{align*} E_{\text{final}} &= E_1 + E_{\text{photon}} \\[1.5ex] &= -2.17\bar{9}89 \times 10^{-18}~\mathrm{J} + 1.63\bar{3}6 \times 10^{-18}~\mathrm{J} \\[1.5ex] &= -5.46\bar{2}9 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J}\\[1.5ex] &= -5.463 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J} \end{align*} \]

Find n

The electron’s final energy must match one of the allowed energy levels. Setting \(E_\text{final} = E_n\) and solving:

\[ \begin{align*} E_n &= -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n^2} \longrightarrow \\[1.5ex] n &= -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{E_n} \\[1.5ex] &= \sqrt{-\dfrac{(1.0973\bar{7} \times 10^{7}~\mathrm{m^{-1}}) (6.62\bar{6}\times 10^{-34}~\mathrm{J~s}) (2.99\bar{8}\times 10^{8}~\mathrm{m~s^{-1}})} {-5.46\bar{2}9 \times 10^{-19}~\mathrm{J}}} \\[1.5ex] &= \sqrt{3.99} \approx \sqrt{4} \\[1.5ex] &= 2 \end{align*} \]

The electron reaches the n = 2 energy level. This 1 → 2 transition is the first line of the Lyman series, called Lyman-alpha (Ly-α), an important spectral line in astrophysics.

Summary

Line Spectra

Atoms emit and absorb light only at specific wavelengths, producing line spectra rather than continuous spectra. Each element has a unique pattern of spectral lines that serves as its fingerprint.

The Bohr Model

Bohr’s 1913 model explained atomic spectra through three postulates:

- Electrons occupy stationary states (allowed orbits) without radiating energy

- Angular momentum is quantized: L = nh/(2π)

- Transitions between states emit or absorb photons with energy ΔE = hν

Energy Levels

For hydrogen, electron energy depends on the principal quantum number n:

\[E_n = -\dfrac{R_\infty hc}{n^2}\]

Negative energy indicates a bound electron. The ground state (n = 1) has E = −13.6 eV. Higher n means less tightly bound (closer to zero).

Emission and Absorption

- Emission: Electron drops to lower level, releasing a photon

- Absorption: Electron jumps to higher level by absorbing a photon with exactly the right energy

Spectral series are named by their final level: Lyman (nf = 1, UV), Balmer (nf = 2, visible), Paschen (nf = 3, IR).

Key Equations

The Rydberg equation calculates wavelengths for hydrogen transitions:

\[\dfrac{1}{\lambda} = R_\infty \left ( \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{f}}^2} - \dfrac{1}{n_{\mathrm{i}}^2} \right )\]

where R∞ = 1.09737 × 107 m−1. The Balmer equation is the special case for nf = 2 (visible lines).