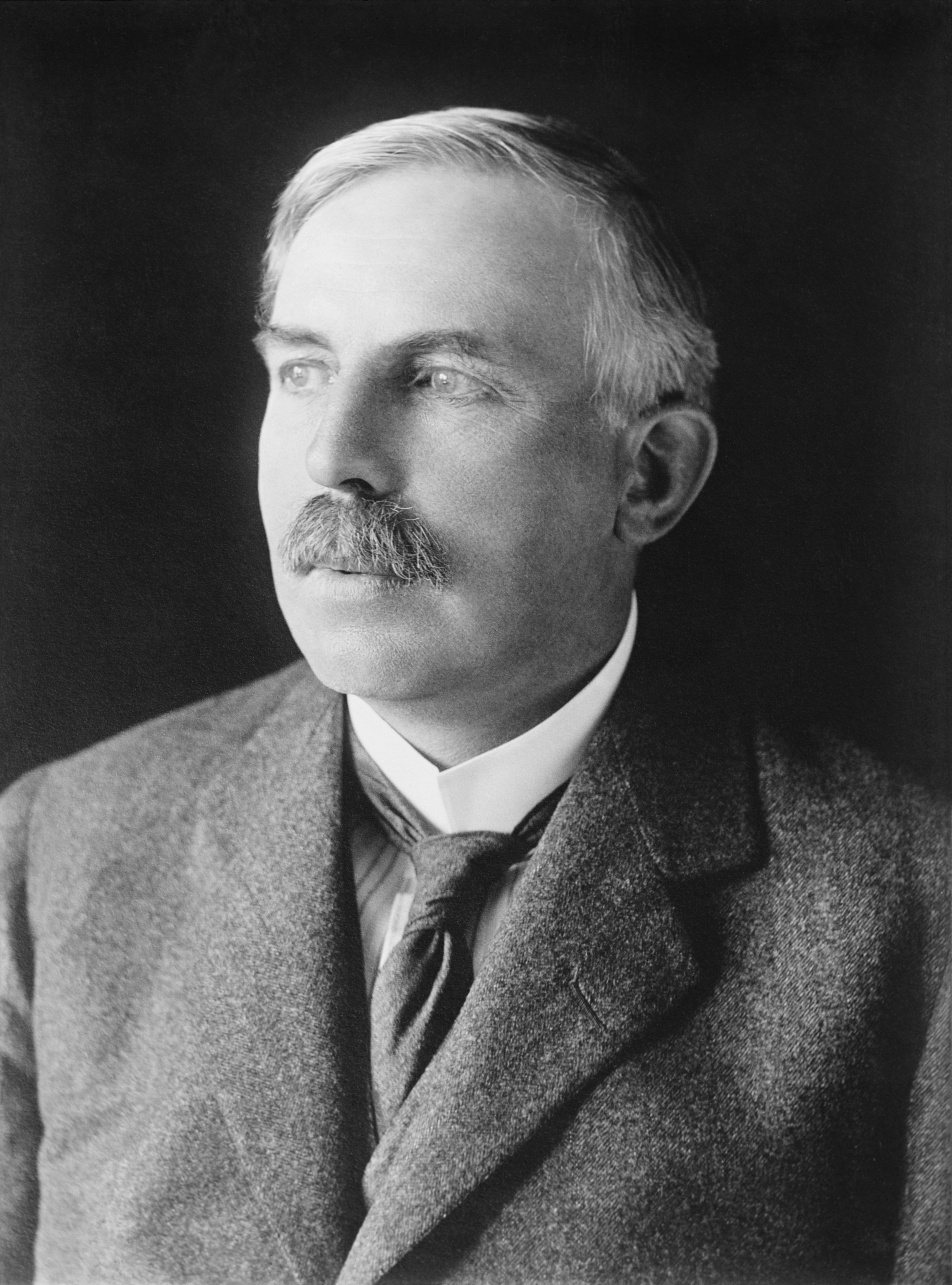

Ernest Rutherford: New Zealand physicist and chemist (1871–1937) (Source: Wikipedia)

The Nucleus: The Atom’s Dense Core

Rutherford and the Discovery of the Nucleus

If J.J. Thomson’s Plum Pudding model were correct, atoms were soft, squishy things. The model proposed that an atom’s positive charge was a diffuse, low density “pudding” that filled its entire volume, with tiny, negatively charged electrons scattered within it like plums.

In 1909, Ernest Rutherford wanted to probe this structure. He designed a landmark experiment carried out by his assistants, Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden. The plan was to fire a beam of alpha particles at an incredibly thin sheet of gold foil. Alpha particles are dense, positively charged particles, essentially the nucleus of a helium atom and are over 7,000 times more massive than an electron. Gold was chosen because it is highly malleable and could be hammered into a sheet only about 400 nm thick, or roughly a thousand atoms from front to back. This is known as the Rutherford scattering experiments (also known as the Geiger-Marsden experiment or more commonly the Gold Foil Experiment).

According to the Plum Pudding model, the fast moving alpha particles should have easily punched through the “pudding” of positive charge. The tiny electrons would be unable to knock the massive alpha particles off course. Rutherford expected the particles to fly straight through the foil, with perhaps a few being only very slightly deflected.

The results, which Geiger and Marsden reported in a 1909 paper, defied expectations. While the vast majority of particles did pass straight through, a tiny fraction, about 1 in every 8,000, were deflected at angles greater than 90 degrees. Some even bounced almost straight back. Rutherford famously remarked, “It was as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you.”

In a 1911 paper explaining these findings, Rutherford argued this could only mean one thing. The atom’s positive charge and the vast majority of its mass were not spread out. They had to be concentrated in an unimaginably small, dense central core, which Rutherford named the nucleus. The strong positive charge of this nucleus would create a powerful electrostatic force, repelling any positively charged alpha particle that came too close.

Calculations based on the deflection patterns revealed that the nucleus was minuscule, about 10,000 to 100,000 times smaller than the atom itself. This led to a new picture of the atom: a tiny, dense, positive nucleus surrounded by a vast region of mostly empty space in which the electrons orbited. This discovery of a dense, positive core led Rutherford to later propose the existence of the proton as the fundamental particle of positive charge within the nucleus. The “soft, squishy” atom was gone, replaced by a miniature solar system. While this planetary model would soon be refined by quantum mechanics, Rutherford’s discovery of the nucleus established the basic architecture of the atom.

It is nearly impossible for our minds to grasp the true emptiness of an atom. The statement that a nucleus is 100,000 times smaller than the atom it belongs to is scientifically correct, but the number is so large it feels abstract.

To make this real, let’s perform a thought experiment.

Imagine you are standing in the middle of the Great Lawn in New York’s Central Park. Let’s scale things up so that a basketball resting on the grass represents the nucleus of a single helium atom. Now, where is the edge of this atom? Where would its two tiny electrons (when viewed as particles) be buzzing around?

They would not be on the edge of the lawn. They would not even be at the boundaries of the park.

If the nucleus were the size of a basketball, the “edge” of that single atom (the outer boundary of its electron cloud) would form a colossal sphere with a diameter of nearly 20 miles. This sphere would swallow almost all of New York City. It would stretch from the northern tip of the Bronx, south past the Statue of Liberty, east into the heart of Queens, and west across the Hudson River deep into New Jersey.

And everything inside that 20-mile sphere (every skyscraper, bridge, subway car, and all of its millions of people) would represent the “empty space” within that single atom. The only thing of any real substance would be the basketball resting on the lawn.

This is why Rutherford’s experiment was so revolutionary. He was firing particles at a target that was, for all practical purposes, 99.999 % empty space. It’s no wonder most of his alpha particles flew straight through. What’s remarkable is that any of them managed to hit something at all.

The Rules of the Nucleus

The Defining Trait: Elements and Atomic Number

The atomic number (Z) is the number of protons in an atom’s nucleus. This number is the atom’s identity card. Every atom with six protons is a carbon atom. Every atom with 92 protons is a uranium atom. Change the number of protons, and you change the element entirely.

We can describe the composition of any nucleus using a standard notation:

\[\large{^A_Z\mathrm{E}}\]

- E is the one or two letter symbol for the element (e.g., C for Carbon, He for Helium)

- Z is the atomic number (the number of protons)

- A is the mass number, which is the total number of protons and neutrons. The number of neutrons can therefore be found by calculating A − Z.

Because the atomic number is redundant with the element symbol, it is often omitted. For example, any helium atom must have 2 protons, so writing \(^{4}\mathrm{He}\) is just as clear as writing \(^{4}_2\mathrm{He}\).

Rutherford’s 1911 discovery established that atoms have a small, dense, positively charged nucleus. But a puzzle remained: the nucleus was too heavy to be made of protons alone. A helium nucleus, for example, has a mass of about 4 atomic mass units but contains only 2 protons. Where did the extra mass come from?

Rutherford suspected the answer. In 1920, he proposed that the nucleus might contain a neutral particle with roughly the same mass as a proton. He called this hypothetical particle the “neutron.” But finding it proved difficult. Without an electrical charge, the neutron wouldn’t leave tracks in detectors or bend in magnetic fields. It was, in effect, invisible to the experimental techniques of the time.

For over a decade, physicists searched without success. The breakthrough came from an unexpected direction. In 1930, German physicists Walther Bothe and Herbert Becker bombarded beryllium with alpha particles and observed a strange, penetrating radiation. They assumed it was high-energy gamma rays. Two years later, French physicists Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie showed that this radiation could knock protons out of paraffin wax with surprising energy.

James Chadwick, working at Cambridge under Rutherford, recognized what others had missed. In February 1932, after just two weeks of intense experimentation, he demonstrated that the mysterious radiation wasn’t gamma rays at all. It was a stream of neutral particles, each with a mass slightly greater than a proton. The neutron had been found.

The nuclear reaction that produced them was:

\[^{9}_{4}\mathrm{Be} + ^{4}_{2}\mathrm{He} \longrightarrow ^{12}_{6}\mathrm{C} + ^{1}_{0}\mathrm{n}\]

Chadwick received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1935 for his discovery. The neutron completed our picture of the atomic nucleus and opened entirely new fields of research. Because neutrons carry no charge, they can slip past the electrical barrier surrounding a nucleus and penetrate deep inside. This property would prove essential for nuclear fission, discovered just six years later, and for the nuclear reactors and medical isotopes that followed.

With this notation, we can precisely describe any nucleus. But here’s an interesting fact: not all atoms of the same element are identical. While every carbon atom has exactly 6 protons, some have 6 neutrons, others have 7, and still others have 8. These variants, called isotopes, are the subject of a later chapter.