The Mole: A Chemist’s Dozen

In everyday life, we use convenient terms to count items. We buy eggs by the dozen (12), paper by the ream (500), and so on. Chemists also need a counting unit, but they work with atoms, molecules, and ions, which exist in unimaginably large numbers. A single drop of water, for instance, contains over a thousand billion billion molecules.

To handle these colossal quantities, chemists use a unit called the mole (mol). The mole is simply a word that represents a very large and specific number of particles.

I have chosen to introduce the unit of the mole before a very central topic in general chemistry: stoichiometry. The utility of the mole seems egnigmatic without understanding stoichiometry. Both the mole and stoichiometry go hand-in-hand.

A simple example can be seen in the following reaction:

\[2~\mathrm{H_2}(\mathrm{g}) + \mathrm{O_2}(\mathrm{g}) \longrightarrow \mathrm{H_2O(g)}\]

The numbers in front of each chemical formula are called stoichiometric coefficients. These coefficients are dimensionless ratios that indicate the relative amounts of reactants and products. Depending on context, they can be interpreted as numbers of particles, moles, or simply as ratios (a coefficient of “1” is often omitted as it is implied). To create 1 mole of water, a combination of exactly 2 moles of H2(g) and 1 mole of O2(g) is required.

Obviously we cannot simply count out a mole’s worth of particles. We will see later on in this section that we can obtain the proper amounts of each substance by weighing them and converting those masses into moles!

Defining the Mole: The Avogadro Number

The mole is the SI base unit for an amount of a substance and is represented with an n.

\[n = \textrm{amount substance (in mol)}\]

A one mole sample of a substance is defined as containing exactly 6.022 140 76 × 1023 of a substance’s constituent particles (such as atoms, molecules, or ions).

This massive number is known as the Avogadro Number (N0). Notice that this number is an integer despite the number of trailing zeroes it has.

\[\begin{align*} N_{\mathrm{0}} &= 602~214~076~000~000~000~000~000 \\[2ex] &= 6.022~140~76\times 10^{23} \end{align*} \]

The Avogadro Constant (NA) is the Avogadro number expressed in reciprocal moles.

\[N_{\mathrm{A}} = \dfrac{N_0}{n} = 6.022~140~76\times 10^{23}~\mathrm{mol^{-1}}\]

Therefore, if you have an Avogadro number of something, you have exactly 1 mole of that thing. Think of the Avogadro number, roughly 602 sextillion, as the “chemist’s dozen.” It is an exact, integer quantity, defined by international agreement.

The Immense Scale of the Mole

It can be difficult to grasp the sheer size of the Avogadro number. To put it in perspective:

- 1 mol of Popcorn: If the continental U.S. were covered in one mole of unpopped popcorn kernels, the layer would be over 9 miles deep.

- 1 mol of Pennies: A mole of pennies stacked on top of each other would create a column 4.5 × 1017 miles high, nearly six times the diameter of our Milky Way galaxy.

- 1 mol of Water: There are more atoms in a single teaspoonful of water than there are teaspoonfuls of water in the entire Atlantic Ocean.

You may encounter an older definition of the mole, which was historically tied to the number of atoms in exactly 12 grams of carbon-12. This definition was practical but had a key limitation: it was dependent on the physical definition of the kilogram and had to be measured experimentally.

In 2019, the definition was updated. The mole is now defined by fixing the value of the Avogadro constant to its current exact number. While this change was fundamental for the science of measurement (metrology), the practical applications of the mole in everyday chemistry remain entirely unchanged.

Visualizing the Mole

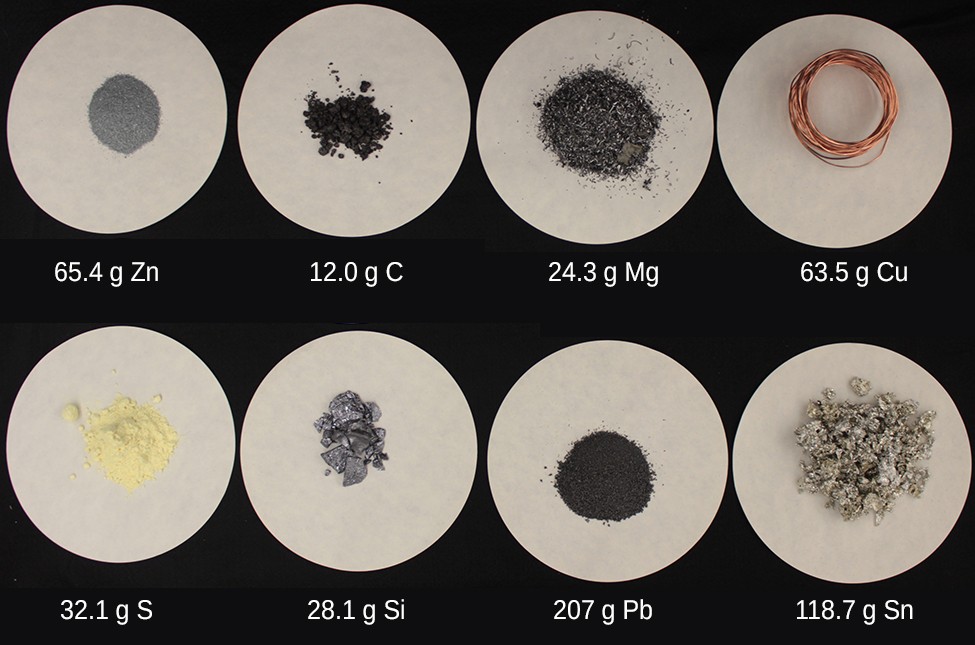

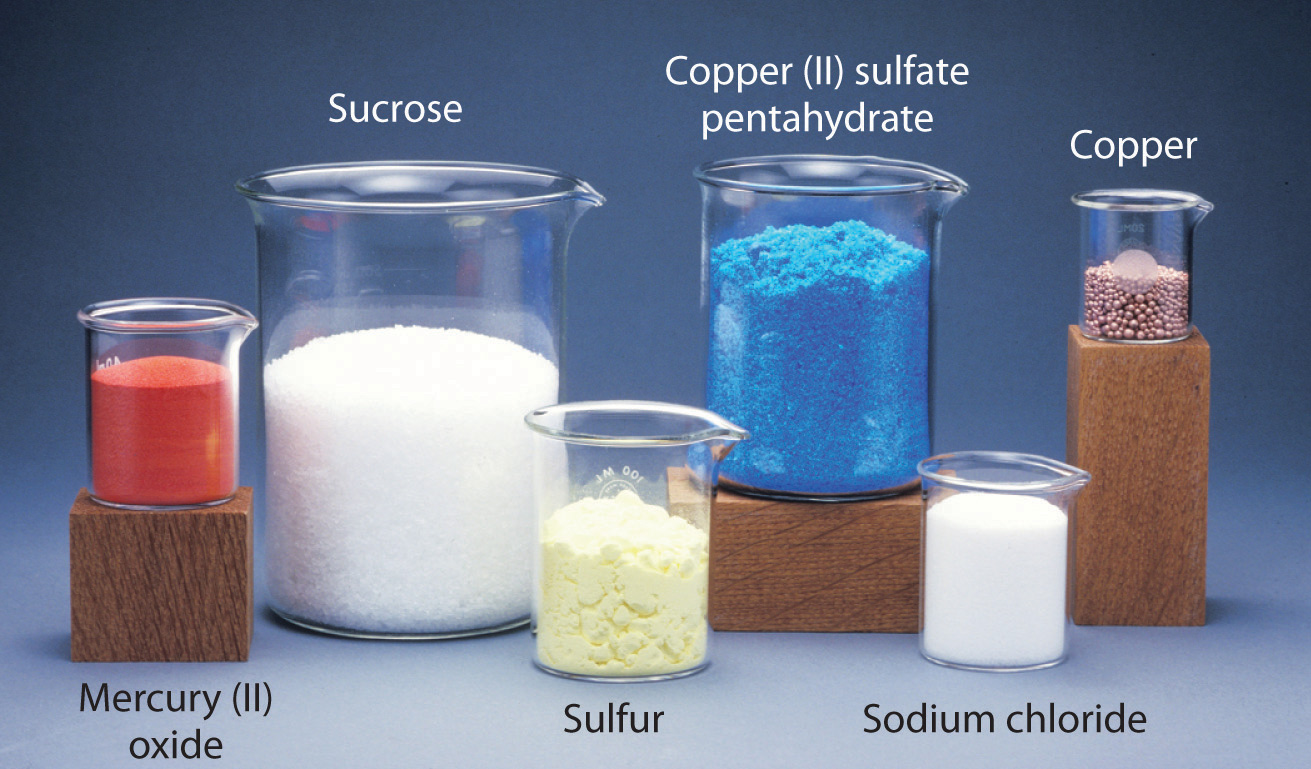

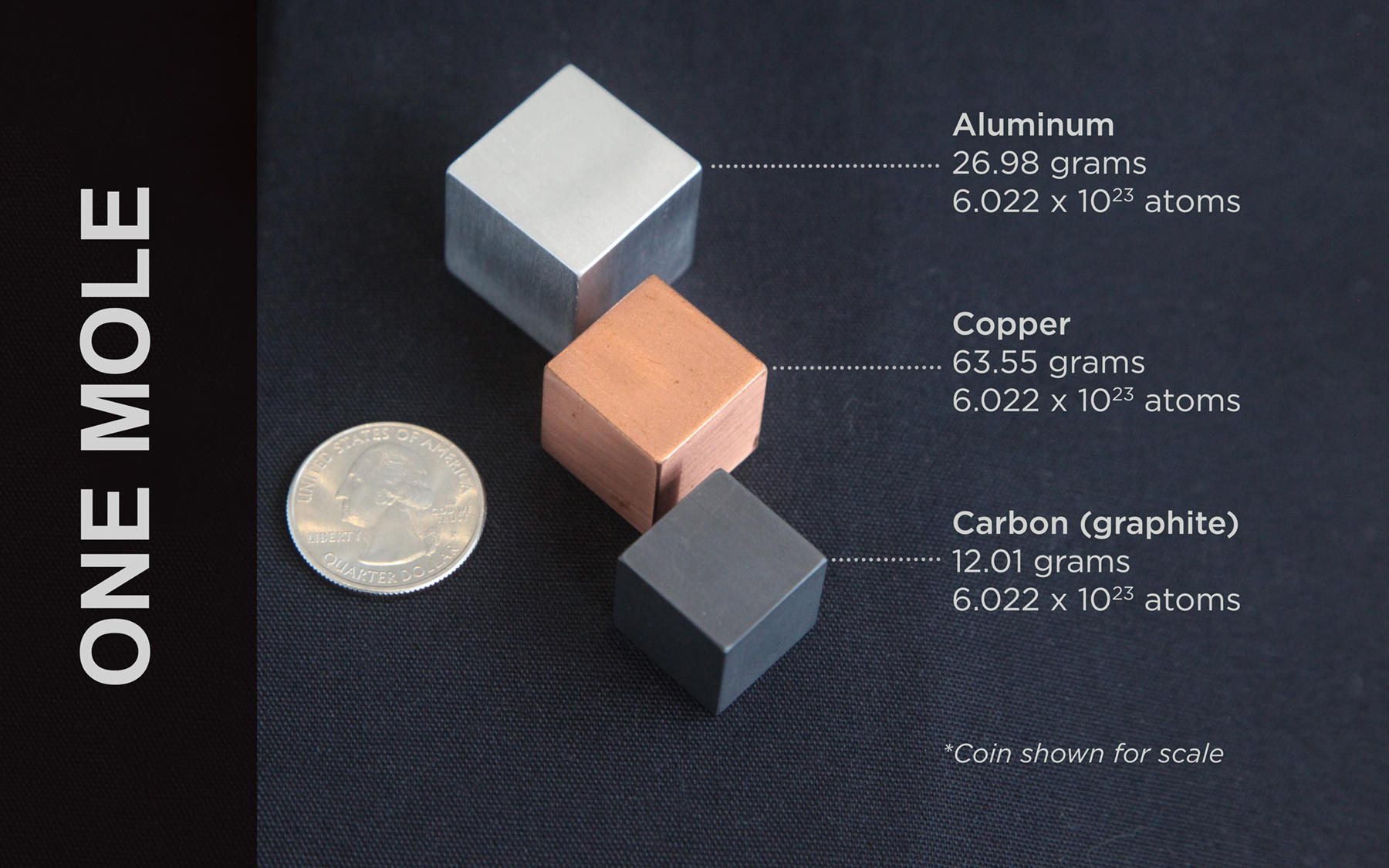

Each individual sample represents 1 mole of the indicated substance. Select a tab to view a different example.

Connecting Moles to Mass: Molar Mass

Knowing that a mole is a specific number of particles is a powerful concept, but its true utility comes from its connection to a property we can easily measure in the lab: mass. The bridge that connects the count of particles in a mole to its mass is called the molar mass. This is an inexact quantity as it is directly tied to mass measurement and is arguably the most important conversion factor in all of chemistry.

The molar mass (M) of a substance is defined as its mass (m) per unit amount of substance (n). It is the essential conversion factor that links the mass of a sample to the number of moles it contains. The relationship is formally expressed as:

\[M(\mathrm{X}) = \dfrac{m(\mathrm{X})}{n(\mathrm{X})}\]

While the formal SI unit for molar mass is kilograms per mole (kg mol−1), the universal convention in chemistry is to express it in grams per mole (g mol−1). Therefore, for most calculations in this text, if the mass (m) is given in grams and the amount of substance (n) is in moles, the molar mass (M) will be in g mol−1.

Molar Mass of Elements

The molar mass of an element is the numerical standard atomic weight value you find on the periodic table but with units of g mol−1. For example,

- The standard atomic weight of carbon, the element, is 12.01.

- The average atomic mass of carbon, the element, is 12.01 u.

- The molar mass of a natural 1 mol sample of carbon is 12.01 g mol−1.

This leads to a crucial and subtle point. A mole is an exact count (the Avogadro number), but the mass on the periodic table is an average. How can an exact count of atoms have an average mass?

The answer is that for a chemical element, we define one mole as a representative sample. “One mole of carbon” does not mean a package with exactly 6.022 × 1023 atoms. Instead, it means:

A collection of carbon atoms that has a total mass of 12.01 g, assuming the sample has the standard natural abundance of carbon isotopes.

For all practical purposes in chemistry, this is the only definition that matters. The molar mass from the periodic table is the essential bridge that allows you to relate the mass you weigh on a balance to the amount of substance (in mol) you can use in a chemical equation. When a problem asks for “one mole of carbon,” it is referring to this 12.01 g package, which is the standard for all stoichiometric calculations.

Molar Mass of Compounds

To find the molar mass of a compound, you simply sum the molar masses of all the atoms present in its chemical formula.

For example, let’s find the molar mass of water (H2O). The formula tells us that one mole of water contains two moles of hydrogen atoms and one mole of oxygen atoms.

- Find the mass of each element:

\[ \begin{align*} m(\mathrm{H}) &= n ~ M(\mathrm{H}) \\[1.5ex] &= 2~\mathrm{mol~H} ~ \left ( \dfrac{1.0\bar{1}~\mathrm{g}}{\mathrm{mol~H}} \right ) \\[1.5ex] &= 2.0\bar{2}~\mathrm{g} \end{align*} \] \[ \begin{align*} m(\mathrm{O}) &= n(\mathrm{O}) ~ M(\mathrm{O}) \\[1.5ex] &= 1~\mathrm{mol~O} ~ \left ( \dfrac{16.0\bar{0}~\mathrm{g}}{\mathrm{mol~O}} \right ) \\[1.5ex] &= 16.0\bar{0}~\mathrm{g} \end{align*} \]

- Sum the masses:

\[ \begin{align*} m(\mathrm{H_2O}) &= m(\mathrm{H}) + m(\mathrm{O}) \\[1.5ex] &= 2.0\bar{2}~\mathrm{g} + 16.0\bar{0}~\mathrm{g} \\[1.5ex] &= 18.02~\mathrm{g} \end{align*} \]

This result tells us that one mole of water molecules has a mass of 18.02 g. This allows us to convert between the mass, moles, and number of particles for any chemical compound.

You can find the number of moles of a substance in a sample with known mass by reversing the conversion! Divide mass (m) by molar mass (M) to get moles. Let’s say you have 500.0 g of water (about 0.5 L). What amount (in mol) of water molecules is in the substance?

\[ \begin{align*} n(\mathrm{H_2O}) &= m(\mathrm{H_2O}) ~ M(\mathrm{H_2O})^{-1} \\[1.5ex] &= \left ( \dfrac{500.\bar{0}~\mathrm{g}}{} \right ) \left ( \dfrac{\mathrm{mol}}{18.0\bar{2}~\mathrm{g}} \right ) \\[1.5ex] &= 27.7\bar{4}69~\mathrm{mol} \\[1.5ex] &= 27.75~\mathrm{mol} \end{align*} \]

How many actual water molecules (N) does this sample contain? Convert moles to number of particles using the Avogadro number.

\[ \begin{align*} N(\mathrm{H_2O}) &= n(\mathrm{H_2O}) ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \\[1.5ex] &= 27.7\bar{4}69~\mathrm{mol~H_2O} \left ( 6.02\bar{2}\times 10^{23}\right ) \\[1.5ex] &= 1.67\bar{0}92\times 10^{25} \\[1.5ex] &= 1.670\times 10^{25} \end{align*} \]

Therefore, the amount of substance in 500.0 g sample of water is 27.75 mol of water which is equivalent to 1.670 × 1025 individual molecules of water. That is a lot of water molecules!

Summary

You should now see the relationship between the measurable quantity mass, the amount of substance (moles), and the actual number of particles. You should be comfortable with converting between these three quantities both forward and backwards. We can simply these relationships in a few formal equations.

Mass to number of particles

\[ \begin{align*} N(\mathrm{X}) &= n(\mathrm{X}) ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \\[1.5ex] &= m(\mathrm{X}) ~ M(\mathrm{X})^{-1} ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \end{align*} \]

Number of particles to mass

\[ \begin{align*} m(\mathrm{X}) &= n(\mathrm{X}) ~ M(\mathrm{X}) \\[1.5ex] &= N(\mathrm{X}) ~ N_{\mathrm{A}}{^{-1}} ~ M(\mathrm{X}) \end{align*} \]

This book extensively uses concise and compact equations that rely heavily on symbols. You can supercharge your learning and mastery of chemistry by becoming comfortable with this form of communicating math and relationships by understanding basic principles behind their presentation.

Consider the following equations that demonstrate the conversion of mass to number of particles.

\[ \begin{align*} N(\mathrm{X}) &= n(\mathrm{X}) ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \\[1.5ex] &= m(\mathrm{X}) ~ M(\mathrm{X})^{-1} ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \end{align*} \]

Step 1: Understand the meaning of the symbols

These equations will use the official IUPAC symbols that represent some physical quantity. For the equations above, the symbols that appear are

- X → an entity such as a particle or a molecule

- N(X) → number of particles of entity X

- n(X) → amount of substance (in mol) of entity X

- NA → the Avogadro number (in mol−1)

- m(X) → mass of entity X

- M(X) → molar mass (typically in g mol−1) of entity X

Step 2: Read the equation like a sentence

\[ \begin{align*} N(\mathrm{X}) &= n(\mathrm{X}) ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \end{align*} \]

Take the first line of our equation. Here we can interpret this equation as a written sentence such as

The number of entities (N) of “X” is equal to the amount of substance of “X” (where n is in moles) times the Avogadro number.

The second line of our equation

\[ \begin{align*} N(\mathrm{X}) &= m(\mathrm{X}) ~ M(\mathrm{X})^{-1} ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \end{align*} \]

can be read as

The number of entities (N) of “X” is also equal to the mass (m) of “X” divided by the molar mass (M) of “X” times the Avogadro number.

Step 3: Recognize “expanded” terms

In a multi-line equation, symbols may often be expanded in terms of other relationships.

\[ \begin{align*} N(\mathrm{X}) &= {\color{red}n(\mathrm{X})} ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \\[1.5ex] &= {\color{red}m(\mathrm{X}) ~ M(\mathrm{X})^{-1}} ~ N_{\mathrm{A}} \end{align*} \]

Notice how the red term “n(X)” is expanded into two terms directly below in the second line of the equation as “m(X) M(X)−1”. This is because we know that moles is equal to mass divided by molar mass!

\[n(\mathrm{X}) = m(\mathrm{X}) ~ M(\mathrm{X})^{-1}\]

These precise equations contain a huge amount of information if you know how to read them properly!

A Note on the Definition: From Carbon-12 to an Exact Number

You might wonder where the convenient relationship between the atomic mass (in u) and the molar mass (in g mol−1) comes from. For many years, it was the result of a very clever definition.

Historically, the mole was defined as: the number of elementary entities equal to the number of atoms in exactly 12 grams of the isotope carbon-12.

This definition was brilliant because it created a perfect, exact link between the microscopic mass scale (the atomic mass unit, defined as 1/12th the mass of a carbon-12 atom) and the macroscopic mass scale (the gram). By definition, the molar mass of carbon-12 was exactly 12 g mol−1.

However, in 2019, the definition was updated to be more fundamental. As we saw earlier, the mole is now defined by fixing the Avogadro constant to an exact, unchanging number. A consequence of this is that the mole is no longer tied to the mass of carbon-12. The relationship between atomic mass units and grams per mole is now an experimentally determined value, not an exact one by definition.

For all practical purposes in a chemistry course, this change is too small to notice. You can and should continue to use the atomic mass on the periodic table as the molar mass in g/mol with confidence.

A Deeper Look: The Molar Mass Constant

For those interested in the highest levels of measurement science (metrology), the subtle shift in the 2019 definition is captured by a quantity called the Molar Mass Constant (Mu).

The Molar Mass Constant is the conversion factor that relates the mass of a single particle (measured in atomic mass units, u) to the mass of a mole of those particles (measured in g mol−1). It is formally defined by the relationship:

\[M(\mathrm{X}) = M_{\mathrm{r}}(\mathrm{X}) ~ M_{\mathrm{u}}\]

- Before 2019: Because of the carbon-12 definition, the Molar Mass Constant was exactly 1 g mol−1 by definition.

- After 2019: Now that the mole and kilogram are defined independently, Mu, is an experimentally measured value with an extremely small uncertainty. Its official CODATA value is approximately 0.99999999965(30) g mol−1.

This tiny deviation from exactly 1 is a fascinating consequence of redefining our fundamental constants, but it only becomes relevant in the most precise thermodynamic and physical calculations. For all laboratory chemistry, treating it as exactly 1 g mol−1 is perfectly acceptable.